Index

Mots-clés : accident, ajustement, bande dessinée, expérience, humour, manipulation, nature, programmation, régimes interactionnels, texte

Auteurs cités : Diana BARROS, Jean-Maie FLOCH, Eric LANDOWSKI, Jean-Paul PETITIMBERT

- Note de bas de page 1 :

-

Cf. Les interactions risquées, Limoges, Pulim, 2005.

In this short article, I would like to present a modestly unorthodox approach to Landowskian sociosemiotics, particularly to its regimes of meaning and interaction1. What exactly do I mean by “unorthodox” ? The theory of regimes of meaning was conceived and has been developed as an interrogation into meaning-making beyond the confines of standard textual semiotic analysis. This extension in scope is especially relevant with regard to close reading : since the Landowskian regimes of meaning constitute an outline of the most general concepts for semiotic research, reflection and action, they seem to be removed from textual minutiae. On the other hand, they have been defined without specifying a particular region of understanding they are supposed to model. My own semiotic practice is mostly limited to textual analysis, hence I have been intrigued by what the regimes might offer in terms of explicating and interpreting texts.

I have found that it is, in fact, possible to transfer the model to textual analysis. In close analytic reading of texts, we can catch a glimpse of how the regimes of meaning and interaction are projected forth in surface textual forms. The model is efficient if employed as a hermeneutic grid for describing how the surface structure of the text is organized with regard to fuzzy cultural notions of value, hierarchy, experience, enunciative praxis etc. Thus we are treating the regimes as structurally interrelated general semantic notions of how being in the world might be understood within the confines of culture. As the concepts used by Landowski to articulate the regimes are very general, the results of textual analysis are rough-edged, but perhaps this is enough for our first attempts.

- Note de bas de page 2 :

-

I am employing the notion of text in a broad sense : in the particular case presented in this article, the text includes a drawing and an accompanying verbal phrase (text properly speaking), which is presented as direct speech of a character in the drawing by using quotation marks and a typical topological arrangement. I consider the making and understanding of texts to be a specific way of making sense of the world and life, distinct from but not unrelated to direct mundane interactions, social practices and lived experience.

- Note de bas de page 3 :

-

Cartoon No. 10 in the slide show here : https://www.newyorker.com/cartoons/issue-cartoons/cartoons-from-the-august-19-2019-issue?verso=true

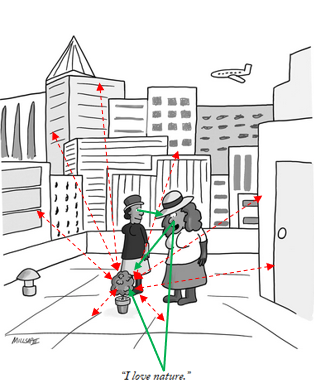

In order to demonstrate the way I conceive of a “transfer” of the regimes of meaning and interaction into textual analysis, I shall present a brief reading of a popular comic text2. My rather randomly chosen example is I love nature, a New Yorker Cartoon of August 19, 2019, by Lonnie Millsap3. The cartoon by Millsap is a slightly sarcastic take on issues related to our present preoccupation with being human, making sense of our connection to nature and of the “Anthropocene”.

1. A very regular environment… (Programming)

The cartoon is somewhat sarcastic if we take into account a more general practice of rooftop gardening in the metropolis that is New York, or in some other similar city. We see then that the biological productivity of the practice, whatever it might be in fact, has been reduced by the artist to a single flowerpot with a tiny tree. We can also see that in contrast to this tiny tree, the city has been rendered by the artist as a pure “concrete jungle” — all we can see are high-rise buildings. Even the door to the rooftop, which could be made from wood, is not distinguished from the buildings by any special perceptive quality of its surface.

These simple observations provide for a broad horizon of meaning in terms of the regimes of meaning and interaction. First, the “concrete jungle” of the city is easily interpreted as a casual space-time of programming. This reading holds with regard to the distribution of plastic features : the whole of the city is drawn in straight lines and clear-cut angles, in repetitive shapes. It is a lived space-time of regularity. Putting aside the tree and the human actors, which can be seen as inherently distinct from the city as such (we can take them for figures of actors and everything else for figures of space), there are only four noticeable exceptions to this rule of regularity that differ in their degree of exception : they are the triangular rooftop, the airplane in the sky, the round doorknob and what seems to be a convex gas chimney on the left side of the rooftop.

These four exceptions can be accounted for with three explanations. 1) The triangular rooftop is a marker of the very summit, the highest realization of the life of regularity. It is just as regular as the straight-angled buildings, but is opposed to them in a plastic semi-symbolic categorical sense (pointed vs blunt), which is an expression of hierarchy in terms of meaning. 2) The airplane is a complexification of the principle of programming. It is a composite object and thus a result of an operative practice of making things. It is a more developed form of regularity that brings a sense of life into the otherwise lifeless cityscape. In other words, regular space-time is not necessarily static, programmed entities are capable of movement.

3) The doorknob and the gas chimney are, in contrast to the first two exceptions, foreign to the regime of programming. They are compositionally part of another series of elements that is best associated with the sensitive regime of adjustment. For this reason I will discuss them separately further on. As for their role in reading the drawing as a casual space-time of regularity, these two elements are, first of all, points of surplus of sensuality. Their round, convex shapes are disturbing in the text dominated by straight lines and corners. In the process of reading the drawing, they disturb the incorporation of everything which is the city under the regime of programming and oblige us to reconsider what the space-time of the image really feels like. For such reconsideration to be fruitful, we need to construct new meaningful configurations of elements.

2. “Would you look at this tree, and at me !” (Manipulation)

Looking at the drawing again, we see that the situation it portrays is based on an intuitive contrast between the casual space-time of regularity and the tiny tree on the rooftop. Even more, the tiny tree is introduced to us, the readers-viewers of the cartoon, as the focal point of the drawing. The focal position of the tree is determined by several aspects. Firstly, it is, indeed, in the relative centre of the horizontal compositional axis (I have marked the position of the tree with regard to its surrounds with red arrows). Secondly, it is the only representative of “nature” in the drawing (note that in the drawing even the sky is only virtually depicted). Thirdly, it is in the centre of attention in the intersubjective situation : the two women who are partners in gardening constitute an intersubjective field and their joint attention — together with ours inasmuch as we interest ourselves with their interests — is directed towards the tree by the woman who is the enunciator of the words written in the lower part of the cartoon. Fourthly, the tree is the figurative (metonymic) referent of the linguistic expression “I love nature” (I have marked this focus of intersubjective attention with green arrows).

This four-fold focalization of the tiny tree invites further consideration. It is first and foremost a question of how these semiotic folds are organized in the process of attributing value to the tree. Since the tree is a static object of dinstinctive shape in the center of other objects markedly similar to each other, there is reason to believe that the enunciation in the drawing is indicative, as in “look at this tree !”. And then there is an actual character in the drawing itself doing just that : a woman is, indeed, looking at the tree. The two acts of looking are not identical because they do not ascribe the same value to the tree. This difference in value is manifested by two ways of making the tree central. For the subject of the first act of looking, the enunciator arranging multiple objects and characters in the drawing, the tree is the relative centre, while the actual centre of the horizontal axis of composition is empty. Shifting the tree slightly towards the left is a semi-symbolic act of enunciation. Quite literally, making the tree the relative centre is an expression of its relative value. By choosing this position for the tree, the implicit enunciator takes its distance from the two characters, who are the composite subject of the second act of looking. For them, the tree is, indeed, the actual and only centre of attention and experience, hence its absolute value.

Thus we face two acts of attributing value — as relative value and as unique value. As for ourselves, we need to comprehend both acts of looking simultaneously. We are provided with two different positions from which to ascribe value to the tree. This makes its value unstable. In terms of the regimes of meaning and interaction, we project two subjects of manipulation. One of them is the woman depicted in the process of sharing her thoughts and impressions about the tree with another. Technically, this is “vertical” persuasion that concerns identity : in this sense, the woman is saying something like “I am such a nature lover”. For her and her partner, the tree is the centre of attention and a sort of mirror for reflecting on their identity. The other subject of manipulation is the enunciator. This subject suggests we keep at a distance from what the first subject says about the tree and herself. By mediation of this other subject, we are able to see the broader picture and the tree as one object among many. While it is markedly different form some of these, it is also similar to others ; it is not unique and not a unique locus of identity.

- Note de bas de page 4 :

-

For a classic analysis in this vein, see the analysis by J.-M. Floch of R. Doisneau’s photography “Fox-terrier sur le Pont des Arts”, in id., Les formes de l’empreinte, Périgueux, Pierre Fanlac, 1986.

Thus the cartoon as a whole is highly manipulative : compositionally, we are persuaded to look at the tree as a relative centre ; in the world of the drawing, the tree is looked at by a character and perceived as an actual centre ; and this character, in speaking about the tree, is linguistically persuading another character of her own identity. We, as viewers, are entangled in a series of manipulations4. This series is what makes the tree the focal point of the drawing and suggests that the value of the tree is not stable. We might interpret this series as a plastic and narrative construction of doubt, incredulity or some other similar modal state of mind. And it might be important to rephrase this statement in a simpler form : we can practice doubt by looking at cartoons.

3. Not all wonder is wonderful (Accident)

The next step is to consider the predetermination of the value of the tree with regard to its nonhuman surrounds, which I have already described as a casual space-time of regularity and programming. First of all, this is a plastic determination : with regard to its straight-lined and straight-angled surrounds that make up the city, the tree is a plastic exception. It is not just standing there at the focal point — instead, it is discovered by us and the woman as “something different” against a background of sameness. If we combine this layer of meaning with the previous one and allow that it is the woman speaking who is the one to actually discover the tree, we see that as a subject she is interacting with the world twice. One interaction is that of manipulation, speaking to the other subject. Another interaction is discovering a tree in the midst of the “concrete jungle”. This latter interaction is not manipulative since the tree is not a subject. Instead, this is a happy accident.

- Note de bas de page 5 :

-

For example, see Diana de Barros, “Les régimes de sens et d’interaction dans la conversation”, Actes sémiotiques, 120, 2017. In the section dedicated to the regime of accident, de Barros provides a revealing example of a failed interview by a schoolchild interviewer : instead of answering, the distinguished and disgruntled respondent starts asking questions himself. The schoolchild is embarrassed and gives in, obediently answering the questions of the interviewee. The roles are reversed and the interview a failure. The failure begins at the very moment that the schoolchild gives in, and that is his own contribution to the failed interview. The subject is part of the accident that has befallen him.

Why so ? Judging from their clothes, we see clearly that the women are not first-timers when it comes to trees on roofs — I mentioned in the beginning that the cartoon concerns rooftop gardening. Thus, the accident is not about discovering a tree on a rooftop in general, as in some post-apocalyptic scenario. I see this as an important point to make with regard to accidents and meaning in general : since the regime of accident is a regime of both interaction and meaning, the subject facing the accident is just as important as the things that happen. In other words, the subject is co-creator of accidents5. This helps us understand in what sense the tiny tree is accidental : it is accidental inasmuch as it surprises and delights the subject, makes her wonder as it arouses in the depths of her being — the originary place of all the accidents of the inner life of the mind — her “love for nature”, a love which she then interprets in terms of manipulation as part of her identity.

I should also stress that it is reasonable to see the discovery of the tree by the woman as pertaining of the regime of accident only if we take heed of the plastic contrast between the tree and the city. If the contrast were nonexistant, if, for example, the tree were found in between other green public spaces or in an actual garden, we would have less reason to take the statement of the woman for an explicitation of the experience of discovery and wonder. If she were in an actual garden, we might think she is expressing a special mood. But a single tiny tree is enough for this gardener to be taken over by a certain enthusiasm. The plastic contrast makes her encounter with the tree explicitly and deliberately salient : for the woman, this tree is something entirely and delightfully different from her general environment.

- Note de bas de page 6 :

-

There is possibly a broader horizon of meaning here, as the hyperbolised space-time of regularity is also a hyperoble of insignificance. In terms of human interaction with nature, it is “pre-anthropocenic”, i. e. based on a pre-established distinction and hierarchy between anaesthetic ideal laws for controlling, exploiting and distancing ourselves from “nature”, and accidental encounters ranging from harmless delight to the extreme wanderings of romantic explorers. For the notion of the “pre-anthropocenic”, see J.-P. Petitimbert, “Anthropocenic Park : humans and non-humans in socio-semiotic interaction”, Actes Sémiotiques, 120, 2017.

- Note de bas de page 7 :

-

This enunciative strategy is probably based on an implication, by the enunciator, that the tree is not “nature” — which could be a reason for the reader-viewer to differ with the enunciator. I will leave this possibility unexplored.

At the same time, this is the point at which we as spectators are dissociated from the woman and the position from which she ascribes value to the tree. Dissociation occurs inasmuch as we have a capacity for irony and sarcasm. For we see rather clearly that the plastic contrast offered by the author of the cartoon is greatly hyperbolized — it is characterised by an excess of sameness which should have driven the women mad long ago if they had truly experienced it6. Apparently they haven’t, and we are in a position to see that. We see that in the great scheme of things as portrayed by the author, the tiny tree is but an insignificant occurrence, a joke in the pejorative sense of the word. It does not significantly disrupt the overwhelming sameness of the environment and is no more than an ornament : visiting the tree on the rooftop is far from any sort of return to nature7.

Above, I have already discussed the unstable value of the tree due to its multifold focalisation. Here this instability is brought to a point of rupture in terms of veridiction. By way of understanding the caricatural nature of plastic enunciation, we are led to see that the women are not really aware of the conditions and implications of their shared experience. They are so naïve ! Thus, the tree is a discovery of one kind for the woman — she discovers her inner capacity for wonder in the face of what she calls “nature” ; and of another kind for the enunciator — with the enunciator, we discover that her discovery is not truthful. The juxtaposition of the woman looking at the tree and expressing her unreflected wonder, and of the overall plastic contrast which characterises the tree as an insignificant occurrence rather than event, makes the woman’s wonder questionable. A sarcastic plastic hyperbole overdetermines a naïve linguistic metonymy. This is an interesting instance of dissuasion by experience : we experience the environment and the tree differently and thus find it hard to share the wonder of the character, so instead we disqualify it.

Of course, the same goes for the contents of the woman’s utterance : the tree is not “authentic” nature and thus neither the opposition of nature and the city nor the metonymy “tree” “nature” can truly convince us. This is an interpenetration of regimes of meaning and interaction : we decide the woman is “inauthentic” by ways of sanctioning her utterance under the regime of manipulation, which is only possible because we have a different experience of what constitutes her personal accident. And this is possible because we have grasped the hyperbole of programming with regard to which the poor little tree is no event. In the process of understanding, simultaneous interactions under different regimes interpenetrate, coordinated by our sense of sarcasm.

4. Recapitulation

So far in my close reading of the cartoon by Millsap, I have made use of three regimes of meaning and interaction — programming, manipulation, and accident. The introduction of programming by plastic means summons a cliché of the “concrete jungle”. The same plastic structure leads to the opposite regime of accident, as a complete break from the cliché. This break is then evaluated and communicated intersubjectively under the regime of manipulation. In their interpenetration, the different interactions invite an assessment of their truth value.

This seems to have been doubly efficient. First, discerning the manifestations of different regimes on the surface of the text allows us to see just how complex textual composition is, despite a limited number of modalities of expression and a rather simple form. The text comes to being in a process of exploiting and integrating various tendencies of interaction and apprehension. For example, we sense a hyperbole in the depiction of a programmed “concrete jungle” and are doubtful of the accident that is supposedly an escape from this predicament. In both cases text comprehension requires some kind of recall of prior experience which we are led to reevaluate and restructure with regard to the difference between what a character says and what the large-scale manipulation suggests.

The different regimes are not just recognized, they are also pre-interpreted and re-interpreted as different ways the world is or might be under particular circumstances. In other words, the cartoon is also a “reading” of programming, accident, and manipulation. Discerning the regimes in textual analysis opens up a broader hermeneutic horizon, allowing us to relate the text to our understanding of the world and uncover the text’s formative potential. When we read the text, we exercise our capacity for these different types of understanding.

5. Dimensions of the humorous (Adjustment)

The textual analysis presented above is mostly a description of doubt and sarcasm in the cartoon by Millsap. Semiotically speaking, in this cartoon, doubt and sarcasm are manipulative. We are presented with a woman expressing her wonder at a tiny living tree in a big monotonous city, and yet several cues lead us to disqualify her wonder as unconvincing, inauthentic, something we have “seen through”. We know better than the silly woman, we are able to rightly judge her dissociation from the world, we distance ourselves from her in the very heart of her being, i. e. in the midst of her wonder itself. We disqualify her wonder, the contents of her speech, her conception of the world and of her own identity as a nature-lover. First comes doubt, then comes sarcasm.

But I think we are right to sense that this cartoon is humorous in a broader sense. It feels lively and jovial. How does that come to be ? I am pretty certain that in terms of regimes of meaning and interaction this sense of the humorous is best revealed by discussing the textual markers of adjustment. Let me return to the abovementioned series of round and convex elements and indicate them in the drawing with brownish arcs.

I believe it is safe to say that the textual forms of adjustment in this drawing are the pivot of its conventional “cartoon” humorousness. In the drawing, adjustment is engendered by repetition of delicate shapes that are never the same. It is repetition through variation : the shapes, disseminated throughout the horizontal axis of the drawing, recall each other in their convex and round delicacy, and each of them modulates this feeling of delicacy simply by being moderately different from the others. Another important feature of this series is that it interconnects different kinds of elements : a knob, hats, hair, noses, breasts, shoes, human figures, a tree, a chimney… The interplay of convex and round shapes is a praxis of plastic enunciation that establishes poetic correspondences between the seemingly unrelated things of the world. The convex and round shapes resemble each other throughout the horizontal series, but they are not regular. Nor are they equivalent : we could not exchange the shapes of the chimney for those of the tree or the doorknob. Instead, they follow up on each other, extend each other, prolong their own co-resemblance. The world of the drawing is thus infused with a certain self-generating élan. This plastic praxis is visibly autonomous from the other parts of the drawing made up of straight lines and corners, and abstract subject-object entities engaged in wonder, doubt and sarcasm.

Adjustment as enunciative praxis relates the drawing to the cultural tradition of humorous cartoons. The sensitive interplay of corresponding shapes provides for a certain delicacy, a joyousness, a good-natured outlook towards the world. Obviously these moods have not been created in the drawing ex nihilo. They are drawn from the broader inherently playful tradition of “cartooning” the progress of the world we live in. Once again, employing the regimes of meaning and interaction in textual analysis allows us to relate the surface structure of a text to a broader understanding of the world.

It is interesting how, in this case, the locus of adjustment seems to be both integral to the drawing and removed from the elaborate cultural criticism of illusions with regard to “nature”. The interplay of delicate shapes establishes an attitude with regard to the drawing as a whole, its place in the broader culture and in everyday life. This distinct plastic praxis makes the sarcastic critical part of the drawing more light-hearted and somewhat ambiguous, situates the “message” of the cartoon in between politics and entertainment.

In a more abstract thematic sense, there is also adjustment in the lady characters’ choice of clothes. We can see that they are well-dressed for gardening, with their gloves and what seem to be rubber boots… This is part of a semiotics of sensibility in the sense of how one feels with clothes like that, with one’s rubbery fingers in the ground, the sun shining brightly and the grass quietly rustling in the wind… There is, indeed, a sense of the sublime in gardening ! It is also a microcosm of experience. And yet, once again, it’s a microcosm that is totally out of tune with the general, “factual” space-time of the cartoon, the big city, the great plain of sameness. It is in the name of this anachronism and anatopism of adjustment that the true sense of the illusion of nature lived by the characters can be grasped. They are living a fantasy of loving nature in a world of concrete. Much good may it do them !