Prólogo Prologue

Prólogo

A alteridade tem como par dialético a construção e a exclusão social, uma vez que não nos é possível firmar e afirmar um EU/NÓS que não seja no âmbito da comparação ou do reconhecimento que EU não sou o OUTRO e, ainda pior, um outro(sim, com minúsculo). A própria forma de escrever nos remete às representações (Arruda, 1999: 47). No caso da América Latina, antes mesmo de qualquer forma de mídia massiva, desde nossa entrada no universo da cultura ocidental, dita Europeia, formos representados em e por ilustrações e relatos nos quais, visualizados e entendidos fora da singularidade de uma Europa cristã, “un filtro cultural que marcará la alteridad de los colonizados (Al-andalus, los territorios de América, África y Asia) para gestar una clase sometida en cuestión a los intereses de explotación económica mediante guerras de despojo” (Nuñez, 2020: s/p) .

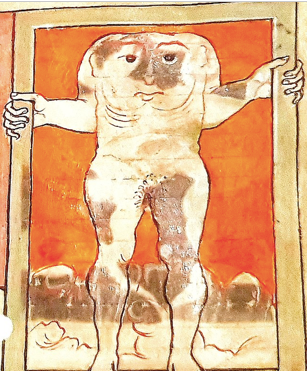

Dessa forma, relatados como seres estranhos, monstruosos e sem deus e em um território rico em sua natureza vegetal e animal e possivelmente em minérios, estávamos prontos para sermos o outro. Não faltaram doutrinas a explicar nossa alteridade. Anos depois, a alteridade africana viria a conformar ainda mais a ideologia que sustentava nossa inferioridade. O continente africano, conhecido muito antes de Nuestra América, será representado, já no século XI, por aberrações como os Blemias, seres encontrados no continente africano (além de Babilônia, Persia e Índia) que não tinham cabeça e seus rostos estavam no peito, mas Nuestra América não ficará sem sua dose de grotesco.

Entre 1595 y 1617 el inglés Walter Raleigh en busca de El Dorado hace una expedición por Sudamérica con el fin de enriquecer a su nación de tesoros. En el primer momento Raleigh llega a la Guayana venezolana donde asegura haber escuchado a testigos describiendo la tribu de Ewaipanomas. A su vuelta en 1599 son publicadas sus cartas, ilustrando de manera fiel sus crónicas de viajes con un grabado en su portada de los Ewaipanomas, seres antropomórficos sin cabeza y rostros en el torso con un tremendo parecido a los Blemias de “Las Maravillas del Oriente” realizados seiscientos años antes (Nuñez, 2020: s/p).

Ilustración - Blemias, de Maravillas del Oriente. ca. 1015-1050. British Library, Londres.

Qualquer que fosse o grotesco da aparência e dos costumes, os espanhóis consideram filhos do deus cristão. Os portugueses discutiram bastante a existência ou não da alma nas populações nativas e, enquanto não chegavam às conclusões, seguiam matando e escravizando as populações justificados pelo colonialismo como missão divina.

Em 2022, quando um estrangeiro pergunta onde estão os elefantes e macacos em uma metrópole como São Paulo, a dialética da produção da alteridade se atualiza nas representações. As múltiplas facetas de uma realidade global demonstram sua perversidade e sua fábula, como afirmava Santos (2001: 20), quando o sul americano ou africano é “acompanhado” [PERSEGUIDO!!] pelo segurança do supermercado europeu pela sua “aparência diferente”.

Alteridade e mídia, uma relação na qual a contemporaneidade reforça a exclusão da Outridade, uma vez que muitos andam com as mídias globais nas mãos, possível de serem acionadas com um toque dos dedos.

Refletir, debater, reforçar a humanidade de cada um e de todos, eis a dialética NÓS – TODOS.

******

Prologue

Alterity has as dialectical pair the construction and social exclusion since it is not possible for us to establish and affirm an I/WE that is not within the scope of comparison or recognition that I am not the OTHER and, even worse, another. The very way of writing leads us to representations (Arruda, 1999, p.47). In the Latin America’s case, even before any form of mass media, since our entry into the universe of Western culture, called European, we are represented in and by illustrations and reports which are visualized and understood outside the singularity of a Christian Europe, as “a cultural filter that will mark the otherness of the colonized (Al-andalus, the territories of America, Africa and Asia) to create a class subject to the interests of economic exploitation through wars of dispossession” (Nuñez, 2020, s/ p).

In this way, reported as strange, monstrous and godless beings and in a territory rich in its vegetal and animal nature and possibly in minerals, we were ready to be the other. There was more than enough doctrines to explain our otherness. Years later, African otherness would come to further shape the ideology that supported our inferiority. The African continent, known long before Nuestra América, will be represented, in the 11th century, by aberrations such as the Blemias, beings found on the African continent (in addition to Babylon, Persia and India) that had no head and their faces were in the chest, but Nuestra América will not be without its dose of grotesque.

Between 1595 and 1617, the Englishman Walter Raleigh, in search of El Dorado, made an expedition through South America in order to enrich his nation with treasures. At first, Raleigh arrives in Venezuelan Guayana where he claims to have heard witnesses describing the Ewaipanomas tribe. At his return in 1599 his letters are published, faithfully illustrating his travel chronicles with an engraving on its cover of the Ewaipanomas, headless anthropomorphic beings and faces on the torso with a tremendous resemblance to the Blemias of "The Wonders of the East" made six hundred years before (Nuñez, 2020, s/p).

Illustration 1 - Blemies, by Maravillas del Oriente. here. 1015-1050. British Library, London.

Whatever the grotesque appearance and customs, the Spaniards considered children of the Christian god. The Portuguese discussed the existence of the soul in the native populations and, while they did not reach conclusions, they continued killing and enslaving the populations justified by colonialism as a divine mission.

In 2022, when a foreigner asks where the elephants and monkeys are in a metropolis like São Paulo, the dialectic of the production of alterity is updated in the representations. The multiple facets of a global reality demonstrate its perversity and its fable, as stated by Santos (2001, p. 20), when a South American or an African are “accompanied” [CHASED!!] by the security of the European supermarket for its “different appearance”.

Alterity and media, a relationship in which contemporaneity reinforces the exclusion of Otherness, since many walk with global media in their hands, which can be activated with a touch of the fingers.

Reflecting, debating, reinforcing the humanity of each and every one, this is the dialectic WE – ALL.